PL: How did the original idea for Man O'War come about, and how did it develop from there?

DJ: It all started with one of SFF Chrons's good ol' 75-word writing challenges. I think the brief had the theme of "desire" or something, so I wrote a story about a sex robot who loved another sex robot, which couldn't be reciprocated because of their programming. It didn't get many votes, but one or two forum members suggested it could be expanded into a short story. So I wrote a short story called Class: Utsukushidesu (which you can read on my website here) which dug a little deeper into themes of transhumanism, emotional intelligence and autonomy.

I went away to think about this some more, and after some time three images kept focusing in my mind: a robot being fished from the sea (pretty derivative of The Bourne Identity, I know), a robot subverting the sexual act, and a return to the water.

The book just fell out of me and, drawing on knowledge built up from my day job, I knocked out the first draft in about seven months. I edited it in another two months and, miraculously, had it accepted for publication after only the second submission.

PL: A small part of Bourne Identity, part-day job (people are going to make a lot of interesting guesses about that one...), part transhumanism... would it be fair to say you drew on a lot of different influences for this story?

DJ: I suppose I did, but the influences were non-fiction. That Bourne reference was literally just the opening image. My day job had a huge influence over the content of the book (people can guess my job if they like, but it's no secret!), and I also used first-hand accounts of a friend who used to work in the oil and gas industry in Nigeria.

Some people have said that there are thematic similarities to things like Paolo Bagicalupi's The Wind-Up Girl and Chris Bennett's Holy Machine, but I've not read either, and wasn't about to start whilst writing Man O'War. Robotics is very much in the public eye right now, and the debates over regulations, ethics and technology (particularly the secondary effects of technology) influenced it more than fiction.

PL: You're certainly right that robotics and its complexities are very much of the moment. What about the influences on your writing itself? How has that developed and how do you see it now?

DJ: I particularly admire Umberto Eco, Tolkien, Haruki Murakami, and Ursula K Le Guin, but I honestly don't think any of those guys influenced Man O'War consciously. Ok, I will say that I decided on the structure of the book - ie one character per POV chapter - after reading A Song Of Ice And Fire. I think it's a very clean way to tell a modern story.

I really put on my Eco hat for a novella I wrote last year, which was a lot of fun, but in general I write what I hear in my head, and emulating somebody else's voice is probably not a good route to go down for a long-term writing career. I recall a review of a Murakami novel once - I think it was Norwegian Wood - that said Murakami evokes so strongly a combination of Raymond Chandler, Harper Lee, Stephen King, and even things like The Beatles, that he has to be considered an original.

Having said that, if readers see echoes of other writers in my stuff, even when I can't, then that's cool too.

PL: Seems like you like your stories to be like a robot - clean and modern! But obviously there's a lot more going on beneath the surface, particularly with the themes you're talking about. How much thought did you put into incorporating those themes and doing them justice?

DJ: I wouldn't say the robots in MOW are very clean, in many ways! There are themes of the ethics of technology – or the humanity of technology, which I suppose is a more Asimovesque way of putting it – in the book, but also themes of fragmentation and symbiosis, with the Portuguese Man O'War acting as the symbol of that. The scene where Naomi explains the nature of the man o'war to Dhiraj in the hotel room is the moment which sort of explains what the whole book is about. I think, once that much is clear, it's possible to revisit and consider the POV characters – and the whole book – in a new way. The thing about theme is that you’re not always considering it; it’s kind of floating there, above the text, so that you’re aware of it as an abstraction, but it’s not fully understood by the writer. It’s like you’re trying to nudge out against the borders of your own understanding. It’s very difficult to be continually thinking of theme in a prescriptive manner when you’re trying to concentrate on believable dialogue and narrative structure. A lot of the thematic elements only became clearer to me after completing the manuscript, when I was editing it.

To be honest, I don't really mind whether or not a reader interprets the book in the same way I do; in fact, I much prefer to hear other people's interpretations of what the book is about than my own! I think the key thing, as a writer, is not to force your themes down your readers' throats so it becomes allegorical or didactic or preachy. There has to be enough wiggle room to allow for the readers' own critical faculties to be engaged. Otherwise it's not literature, it's just dressed up propaganda.

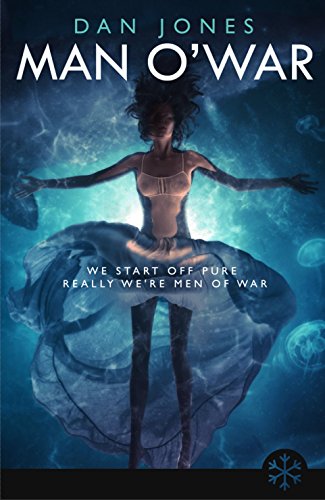

|

| Sometimes you can judge a book by its cover - great work by Snow Books' team |

PL: I stand corrected on the robots!

Have you always been this interested in theme as a writer? Or is this something that's developed for you over time? Come to think of it, how long have you been 'seriously' writing and how do you think you've developed in that time?

DJ: I do have nagging thoughts about the fragmentation of the self, and the atomisation of society as a whole, particularly western society. Until I started writing Man O'War I hadn't figured out a way to work it into a fictional setting, but a robot is a useful vehicle for exploring this topic because it’s understandable as an integrated system of systems.

So it's there, and to an extent always has been. In Eat Yourself, Clarice! one of the major tenets is the fragmentation of the self into different personas (in accordance with psychoanalytic understanding). These fragments are amplified by the proliferation of internet technologies, and manifest through a sort of socialised censorship, whereby we censor the parts of ourselves – and others – we don't want to see. That's quite abstract, but in Man O'War these ideas become tangible, most notably in the form of Naomi, who is a modular system of systems and therefore fragmentable, and also the Portuguese Man O'War creature, which is a colony of tiny creatures working together to make the creature function. And each of the human cast are, in their own way, fragmented, or broken.

I've been "seriously" writing since 2011, but only in the last four years or so have I really started to think about things like theme. Thinking is highly recommended! My take is that in the West we don't think about things as much as we react to them. I think that, as a civilisation, we'd get to a better place if we did rather more listening and thinking, than rushing to condemn. That leads to further fragmentation, and I suppose at some point there's a critical tension point beyond which society cannot divide any further. I can't imagine that being a very good place.

PL: Well that's a very cheery way to look at things. You think there is no potential for humanity's situation to improve through continued fragmentation? I'd have thought giving the various clashing cultures in the space more room to themselves and less need to rub against each other would be good.

DJ: Man, your questions are hard! OK, your question suggests fragmentation is something that we can consciously control, and I'm not sure that's the case. I think fragmentation is more basic than that, it's part of the condition of being human, or the state of being. Freud and Lacan knew this; they suggested we're in fact made up of different parts, a system of systems. In Freud's terms this was famously the id, the ego and the superego. Lacan went further; he suggested we're in fact made up of “partial objects” that we can't initially comprehend. So we make sense of things by learning language, thus ordering ourselves, and that's the first step towards making sense out of the whole world, because the whole world is just as fragmented, and crazy, and weird, and if you can't make sense of yourself then what hope do you have of ordering the rest of it? And all the characters in Man O'War are broken up or fragmented to begin with; they've all had the rug pulled out from under them in some way and they've got to deal with that, or there's no story! So in a sense they're all heroes, whether you think of them as "good" or "bad" in a classical sense, because they’re all trying to make sense of the mad situations in which they find themselves. And I think in a sense any story worth telling has to start with characters who in some way are fragmented (or who become fragmented), so they can make sense of themselves before they make sense of the world.

So to answer the question, no, I think to actively fragment is bad, really bad. The whole sense of being human is to come together in some sense - whether it's in a physical sense, or a social one, or sexual or psychological or religious or some other sense, so as to make sense of things and try and perpetuate this existence by understanding the things we're doing right. And in Eat Yourself I was forewarning that, to some extent, and possibly to a serious extent, that the proliferation of communicative technologies is overriding the need to come together to solve serious puzzles, and I think this manifests itself most dramatically in political spheres; that we can somehow exist in a digital cocoon in which we can self-censor the bits of the world we don't like, rather than deal with those things. Because that's what literary stories are all about, right? Venturing forth from your comfort zone and slaying dragons! Otherwise we all just stay in the Shire and wait for Sauron to just destroy the world. Or worse, we just stay asleep in the Garden of Eden and never even waken into consciousness at all. So there's a serious danger, a fundamentally nihilistic perspective that can arise from encouraging fragmentation.

This is getting way more philosophical than I thought it would!

|

| The Man O'War itself |

PL: Let’s take this a little away from the philosophical and more to the literary, then. You've listed a lot of influences for the story, the majority not speculative fiction. Do you think people view fiction in too fragmented a way and pay too much attention to genre?

DJ: Ok, yes, let's move on. Yes, I think I largely agree with that. I've not been a huge SF reader. I've read bits and pieces: some Heinlein, some Iain M Banks, some JG Ballard, and a few anthologies, but as a rule more recently my genre fiction intake has skewed more fantasy, and after that I just read whatever takes my fancy. And I've thought about this, because it's not the first time someone's asked me why I'm writing SF when I don't particularly read it. I think I enjoy the innate speculative nature of SF, and I suppose I like it most when I'm doing the speculating!

Do people pay too much attention to genre? I think to unpack that you need to think about why people read, because on one level you just read what you like, what pushes your buttons, and there's no real reason why you like what you like, you just do. It's as simple as that. I'm going to ditch the word "genre" for a second, and instead use the word "flavour" instead, because SF and fantasy both have a very strong flavour, but then so does romance, and action, and "chick-lit" (hate that term, but it serves a purpose), and crime, and horror and whatever. But in all of those flavours the writers thereof should still be trying to do the same thing, which is trying to make sense of things and order and orient themselves and their characters in a way that conquers a little bit of the unknown. It's like food. Food can be spicy, or earthy, or rich, or light, or sour etc, but it's all sustenance, it all can be sustaining and make you live to tomorrow ie get you to a place where you can get more food.

And we're foraging creatures, but we don't need to literally forage for food in the modern world, so what do we forage instead? We forage information, and just as we might like different flavours of foods, we might like different flavours of information when presented to us in art or books. So genre alone doesn’t invalidate the power of art and literature to provide that satisfying information, that knowledge that sates our soul. And I get really annoyed when people snobbishly dismiss certain genres, because it only reveals themselves not to be very sophisticated; they haven't really thought beyond the superficial flavour of the genre to what lies underneath, and whether that literature, that food, is worth eating.

|

| An oil refinery from near Port Harcourt - presumably much like one in the book |

PL: I never even realised you were more of a fantasy guy. Are there any areas where you feel this viewpoint and broad scope gives you an advantage or disadvantage as a genre writer? You ever had that moment where someone goes "I like it, but I don't know if it fits a genre well enough?"

DJ: Well I think it's a reasonable assumption to make that the more material to expose yourself to, the deeper your well of knowledge from which you can draw when you want to think and/or create. That makes sense to me because I like to write, and that's what I'm reasonably good at, but also I have a sense that I'm inadequate – not in a self-pitying way, but in a sense that there's so much more to know out there – so it makes sense that one absorbs as much material as possible, so as to keep learning. Rigidly sticking to one genre might not necessarily limit you in your learning - like I said, information is food, and all food (unless it's junk) is nourishing - but you are denying yourself all those other flavours of information. I'm not sure I see any disadvantage in reading as widely as possible!

Do you mean about my own writing? I don't think my audience is big enough yet to have to contend with that criticism, if it is a criticism at all. Genres have to have a loose set of rules, or a rough framework onto which the story is fashioned. Sometimes these things overlap. For example, is Star Wars fantasy or SF? Well, it has advanced technology like spaceships, but it also has magic. Perhaps it doesn't matter, because most of the time people just mash SF and F together into SFF and leave it there, which is a bit daffy really because SF and F are really not that similar when you think about it in terms of their respective archetypes, but anyways... What about Lord Of The Flies? Is it an Boys' Own-style action adventure, or is it literary, or is it fantasy, or even horror? So things start to get a little sketchy when you delve into things. And I like things that way. Things should move about. Fusion food!

PL: I wasn't thinking about the audience, so much as critique partners, your peers in the writing community and so on. I know you've been active there, so what have you taken from writing communities? And since I ask this of everyone - what's the best piece, and worst piece, of writing advice you've ever received?

DJ: I've taken everything from writing communities. I've been extraordinarily lucky to run into a bunch of people with whom I have an affinity and have become great friends, and whose abilities - and different types of abilities - we all respect in one another. It would be very difficult to progress without such things: advice, support, sounding boards, and just general talk. It gives me a sense that it's ok to be doing this, that even if what you're doing isn't "successful" (and that is very much governed by how you define success) that there's still something of huge value involved in the telling, in the doing itself. One thing which makes writers extraordinary is the ability to gee each other up; it's incredibly supportive. Even when we have our disagreements about detail, the general takeaway is that the value is in the doing. It's like tilling the fields, or whatever, the value is in the doing, because what else can you do? Give up? Will Self said that writing is an isolationist pursuit; people who can't stand their own company need not apply, but I think he's only halfway right. Writers are so prone to savage self-criticism, which often leads to the conclusion that the doing is worthless, and has no value, and so you'd better just stop. And that's no bloody good, is it? So finding a group that feels right makes the doing feel worthwhile, and when you're doing, when you're creating, you cannot by definition be self-critical, because you're distracted and screening all that stuff out. And when you successfully complete something, you get serotonin boosts and all that good stuff. And I think doing that without support requires a will of iron, really. So, if there's one piece of advice that I would dispense (and I'm aware that wasn't in the question!) it would be, to write.

Best piece of advice? Bryan Wigmore recently said that (and despite what I've just said about the indispensability of writing groups) one has to retain a confidence in the purity of one's own vision for the work. And I've been thinking about something along those lines for a while, and I could feel it inside, but bloody hell if that guy doesn't have a way of defining it so crisply and cleanly, like everything he writes, the git. But he's on the money; you need to be confident, that if you feel something in the way you're telling the story, then that feeling is right. The difficulty is articulating that dream-like sense of what you want your story to be. And it's in the articulation where you may need the help of others, such as editors and the like, because articulation is exceedingly difficult.

Worst advice? Anything that goes along the lines of "the rules say...", like "don't include a prologue," or "don't infodump," or "don't headhop" stuff like that. I mean, what's the point of fiction if you can't headhop? That just seems ridiculous to me. If you can make it work, then it works, by definition. People have got to have something to latch onto. I tell you what else was pretty dumb advice - and I forget where I got it from - but it was to do with submissions. The advice was to flood the market with submissions. Send your MS and synopsis and whatever off to as many agents and publishers as you can realistically keep track of, and if you throw enough mud, some will stick. And that's just so stupid I can't tell you. I mean, come on, you're sending your MS off to fifty, sixty agents? The only way you're going to do that is by sending off the same bloody letter to each one, without any thought about why you're approaching that particular agent? And I've met agents, I've seen the eye-watering piles of manuscripts on their desks. They're not looking for reasons to accept a manuscript; they're looking for reasons to discard them, because they receive so many of the bloody things.

And with hindsight that's so obvious it makes my head spin. So I figured that a more subtle, tailored approach would be better, and hey presto, it worked!

PL: Indeed it has - for here we are, talking about your first published book. One final question - which one component of Man O'War do you think you executed most successfully in terms of fulfilling your vision? Or, another way of putting it might be; what component are you most proud of?

DJ: Sometimes I'm just pleased and proud that I managed to finish the damn thing, given how much trouble I'm having with my follow up to it. One thing I've learned is that it's no small thing to complete a book in the way you want to. I'm really proud of Naomi. She's my Frankenstein's Monster, or at least my attempted approximation. I think she has layers and layers to her, more than I can understand right now.

You can try understanding Naomi yourself by reading Man O'War, published by Snow Books and available from the usual outlets. Thanks to Dan for doing this - you can find out more about him at his website.